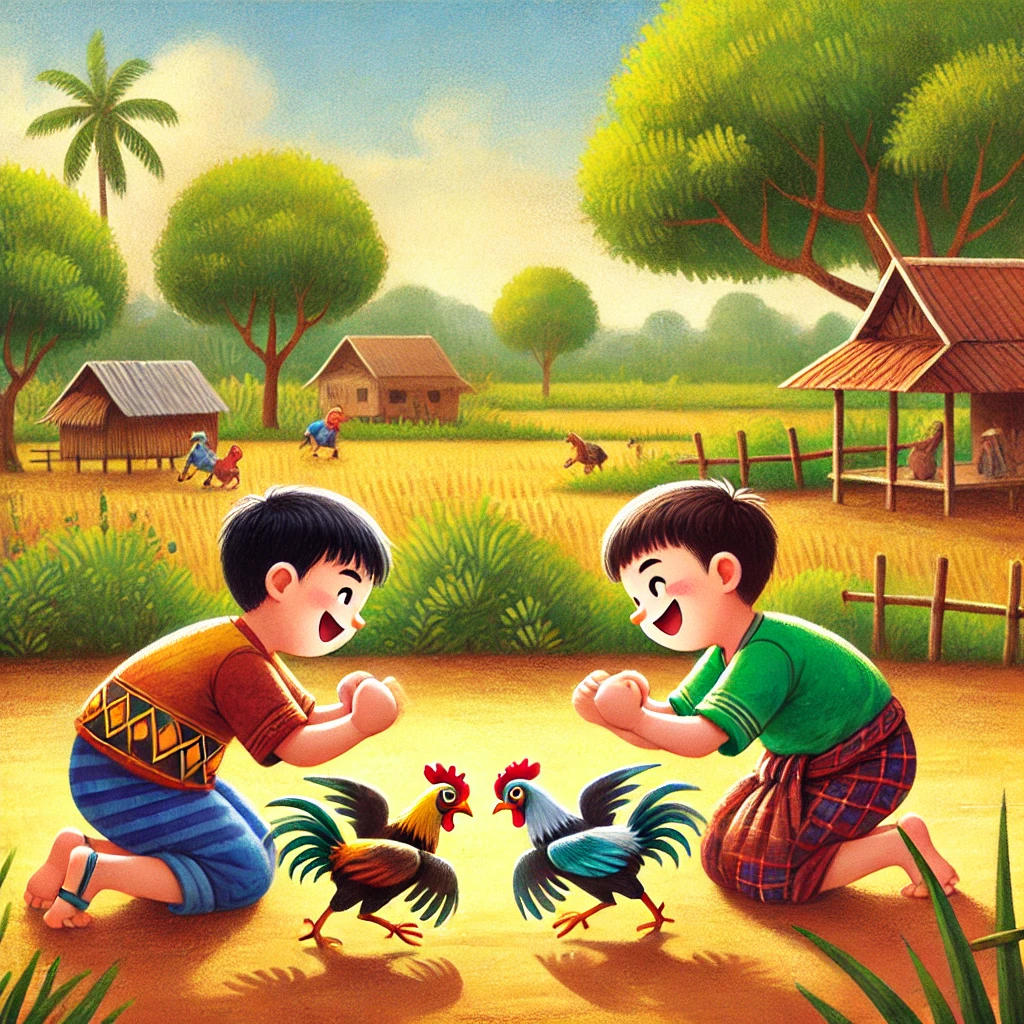

As the first light of dawn breaks, the small rural towns of the Philippines begin to wake. The air is cool, and the muddy paths are alive with the laughter of children. They gather on a dusty open lot, using sticks to mimic the movements of roosters locked in combat. Among them is 11-year-old Kikoy, a boy with bright eyes and a wide smile. For a brief moment, he forgets the hunger in his belly and the weight of his family’s struggles. In these playful games, sabong—the tradition of cockfighting—becomes his world of excitement and escape.

But this innocence masks a harsh truth. These games are preparation for something far more sinister: the “human sabong“, where children are thrust into underground fights that blur the lines between play and survival.

The World Through Kikoy’s Eyes: Joy and Pain in Sabong

For Kikoy and other children like him, sabong has become more than just a cultural tradition. In their world, sabong represents opportunity, a chance to earn money, to gain a fleeting sense of pride, and to briefly escape their impoverished realities.

“When I win, people cheer for me, and I feel proud,” Kikoy says, his voice filled with a mix of innocence and resilience. He recounts the time he won 50 pesos after a fight: “I bought rice for my mother. She was so happy. That day, we ate until we were full.”

For children like Kikoy, victory in sabong brings a rare sense of accomplishment. It offers them a chance to contribute to their families, even if it means enduring bruises, cuts, and fatigue. Yet, for all the joy it may bring, it is a dangerous illusion—one that comes at the cost of their safety and future.

Sabong as Both Play and Danger: The Dual Reality

In underground sabong arenas, the energy is electric. Crowds gather, shouting and cheering as young boys face off against one another. Kikoy and his opponents are barefoot, dressed in worn shorts, their bodies tense with anticipation. To the spectators, it is entertainment. To the boys, it is a mix of play and desperation.

To some children, sabong even becomes a game—a twisted form of fun where applause and attention replace childhood games. Thirteen-year-old Ray, another participant, admits,

“Sabong is exciting. I like it when people call my name. I feel like a hero.”

Psychologists, however, warn of the dangers behind such fleeting happiness. Dr. Maria Santos, a child psychologist, explains:

“For these children, sabong provides a temporary sense of purpose and recognition. In the midst of poverty and neglect, winning in sabong can make them feel valued and important. But this ‘happiness’ is deceptive. Long-term exposure to violence, even in the form of play, desensitizes children and can harm their psychological development.”

The reality is harsh: sabong may bring smiles, but it also leaves scars—both visible and invisible.

Poverty and Exploitation: The Root of Human Sabong

The documentary follows Kikoy home, where his mother sits by a small wooden table, boiling water in a battered pot. Their house, made of thin wood and tin, is barely holding together.

“I don’t know what he does at the sabong arena,” she says softly, her voice heavy with guilt and exhaustion. “I just want him to be safe.”

In impoverished rural communities, sabong becomes both a burden and a lifeline. For families like Kikoy’s, poverty leaves little room for choices. Sending their children to underground sabong matches may seem like an answer to immediate needs—earning a small sum of money for food or medicine—but it comes with devastating consequences.

Organizers of human sabong exploit this vulnerability.

“The kids want to fight. They’re happy doing it. We’re not forcing them,” one organizer claims, shrugging off responsibility.

In reality, these children have no other options. The lure of sabong masks the exploitation beneath it.

The Role of Society: Enforcement and Intervention

Despite laws that protect children from exploitation—such as the Philippines’ Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act—human sabong persists due to weak enforcement and systemic neglect. Local authorities often turn a blind eye, while underground networks thrive.

Legal advocates argue that the solution requires more than just crackdowns:

“We need a comprehensive approach—strict law enforcement, community education, and real support for impoverished families. Human sabong reflects a failure of society to provide alternatives.”

Children like Kikoy and Ray are caught in this failure. While sabong organizers profit, and audiences cheer, the children’s futures slip further away.

A Flicker of Hope: What Can Be Done?

Experts propose solutions to address the root causes of human sabong:

- Stronger Law Enforcement: Authorities must dismantle underground sabong arenas and hold organizers accountable.

- Family Support Programs: Economic aid and education resources can help families break free from the cycle of poverty and exploitation.

- Mental Health Support: Counseling and psychological care are essential to help children recover from the trauma of sabong.

- Community Awareness: Education campaigns can help parents and communities understand the risks and long-term impact of involving children in sabong.

The Final Image: Kikoy’s Dream Beyond Sabong

As the sun sets over the fields, Kikoy sits on a wooden step outside his home, a small rooster perched beside him. He gently strokes its feathers, his gaze fixed on the horizon.

“I like sabong because I can help my family,” he says, “but I also want to go to school. If I study hard, I can get a good job and buy my mother a proper house.”

Kikoy’s words capture the duality of human sabong: a source of temporary joy and hope, but also a symbol of exploitation and lost potential.

[…] 84 Rooster – A locally bred strain in the Philippines with a solid track record in sabong fights and excellent adaptability for various betting […]

[…] through the sabong community. Known as a dedicated referee, he had supported his family of five children through his work in sabong, demonstrating his passion for the sport despite its risks. His family, particularly his eldest son […]